Lessons from the Past: Yellow Fever, the Civil War, and COVID-19

By Ira Spar, M.D.

By Ira Spar, M.D.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are War, Famine, Death, and Pestilence. The last is defined as a contagious and infectious disease, both virulent and devastating: punishment for the wicked and unfaithful. For millennia, the mass movement of human populations altering native populations and the environment has led to pandemics, often war-related. In the calamitous mid-fourteenth century, one-third of Europe died from Bubonic Plague. In the Influenza epidemic of 1918, fifty million died.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a recurrent pandemic, the “American Epidemic” or Yellow Fever, killed thousands. Lucrative trade beginning in the late seventeenth century led Europeans to transport slaves from West Africa to North and South America and the Caribbean, bringing with them a deadly febrile illness with mortality rates over 25 percent. High debilitating fevers and muscle pain were followed in some cases by jaundice, black vomit, and convulsions. The last three signs usually proved fatal. In the late eighteenth century, the disease struck the northern American cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia as well as seacoast towns in Connecticut. By the early nineteenth century, the disease was limited to southern ports, returning with vengeance in the 1850s to New Orleans with six episodes of fearsome attacks over 12 years. The fiery maw of this disease was fed by waves of susceptible Scottish, German, Dutch, and Italian immigrants.

Doctors of this era felt they were the pinnacle of medical science. However, the existence of bacteria, fungi, and viruses had not yet been discovered. Surgeons washed neither their hands nor instruments and wore neither mask nor gloves. Asepsis and anti-sepsis were in the future. There were no infusions of fluids or transfusions of blood. That mosquito was a vector for disease delivery would be discovered at the end of the century. The viral etiology of Yellow Fever, also called the Saffron Scourge or the Newcomer’ Disease, was unknown. The treatments offered were unsuccessful and even harmful. Despite clear evidence that heroic treatment with mercury, quinine, rubefacients, bleeding, and cupping failed, their usage persisted. As one wag declared, “as the shelves of the apothecary emptied the cemeteries filled.” A constant was the abject terror that struck populations as attacks occurred. Those who could leave did so. Most doctors and nurses stayed and often suffered the consequences. Businesses closed. Newspapers reported the appearance of disease late in its course, aligning with business interests to prevent panic.

Public health boards were created to deal with these epidemics amidst a divided medical community. Most physicians believed the cause was decomposition of organic and inorganic matter in filth-ridden wharves and streets that produced a gaseous or miasmatic “perfidious effluvia.” That is Latin for, “we don’t know.” If the disease came from within, the solution then was to clean up the “filthy” cities. Sanitary measures always make sense. Others correctly saw the disease coming from without, perhaps from sea-faring ships, and advised quarantine as the solution. Most American officials, medical and military officers, businessmen and industrialists were opposed to quarantine. Britain, whose navy ruled the seas, joined political forces to keep trade routes open and denounced quarantine as useless and even counter-productive.

As the disease settled in the south, those with experience saw quarantine as the best approach and attempted to buck political opposition nationally. The anti-contagionists noted that sick patients transported to outside hospitals never transmitted the disease. Even those who shared their bed and sheeting with spouse or other partners showed no further transmission. Fomites such as clothing, towels, and bed sheets also did not spread disease. Economic and political factors played a role as to which policy would be enforced.

Social determinants were critical, as yearly infusions of immigrants poured into America with no immunity. They fell by the thousands. They were poor, living in crowded and unsanitary conditions, and as such were blamed for their disease. This was seen as the “Newcomer” or “Immigrant” disease. Previous exposure granted life-long immunity to the blue bloods or upper-class residents who viewed the sick as unfortunates, but given their loose and lascivious immoral lifestyle, what else could be expected?

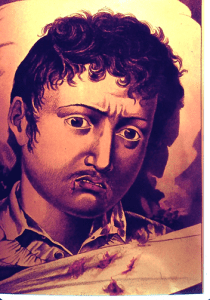

As the Civil War began, ministers beseeched their Lord on Sunday sermons to dispatch Yellow Fever epidemics because, “What the Confederate bullets do not stop, the Yellow Jack will.” Union soldiers, having no prior exposure to the disease, would be vulnerable. The Union Navy blockaded the Confederacy, thus eliminating infected ships from effectively entering a national quarantine. In New Orleans, General “Beast Butler” enforced a strict thirty-day quarantine, eliminating the disease that had decimated populations for twelve years. The Fifteenth Connecticut Volunteers from New Haven and the Sixteenth Connecticut Volunteers from Hartford who were stationed in Newbern, North Carolina, were struck by a Yellow Fever epidemic in 1864. Military doctor, patient, and civilian sufferings and observations are detailed in letters sent home. The fear, uncertainty, gloom, and desperate attempts to bury the dead and treat the living are backdrops to burning barrels of turpentine and the cascading roars of cannons used to drive off the sickly humors, which resulted in a black, foul-smelling haze.

A recent patient remarked as we discussed the coronavirus epidemic, “It’s hard to know who to believe.” The science of the nineteenth century was limited and confusing. As Shakespeare noted in The Tempest, “What is past is prologue.” Many features of today’s pandemic happened before. Economics, politics, class differences and a lack of scientific data demand sensible leaders with humility to recognize that, despite gaps in our knowledge, national policy is required to lead us out of the wilderness into the promised land.

If surgeons can learn to wash their hands and wear masks, perhaps others can do the same.

About the Author

Ira Spar, M.D., is an Orthopedic Surgery Specialist in Plantsville. He earned his medical degree from George Washington University School of Medicine. He is a past President of the Hartford Medical Society, a Board Member of the Society of Civil War Surgeons, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. He served as a U.S. Army battalion surgeon in the Vietnam War and currently lives in Farmington.

Ira Spar, M.D., is an Orthopedic Surgery Specialist in Plantsville. He earned his medical degree from George Washington University School of Medicine. He is a past President of the Hartford Medical Society, a Board Member of the Society of Civil War Surgeons, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. He served as a U.S. Army battalion surgeon in the Vietnam War and currently lives in Farmington.

Dr. Spar is the author of two books, New Haven’s Civil War Hospital: A History of Knight U.S. General Hospital, 1862-1865 and Civil War Hospital Newspapers: Histories and Excerpts of Nine Union Publications. Both titles are available on Amazon or through McFarland Publishing. Dr. Spar is currently working on a new book about Connecticut’s War Governor, William A. Buckingham.