Reflections from Influenza with Coronavirus

Reflections Comparing the Deadly Influenza Pandemic in 1917-1918 with the Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020

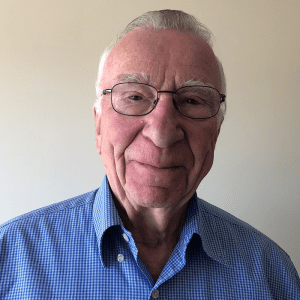

By H. David Crombie, M.D.

There was an obstetrician/gynecologist in my hospital whom I greatly admired for the purity of his human interaction and kindness with his patients and his colleagues. Seeking the inspiration for these special attributes, they might be discerned over years of observation and from stories provided by the individual himself. Upon this backdrop in our friendship, I would submit that a source of this man’s dedication to his calling, and the empathy with which he approached the ill patient, lay in his experience with his doctor/father during the devastating flu epidemic in Upstate New York in 1918.

He was nine years old and often accompanied his father, a family doctor, making house calls, day and night throughout his “territory”, in his horse and wagon or a Model T Ford. Unlike the profile of present-day fatalities from COVID-19, the victims were not found chiefly AMONG the elderly and comorbidly infirm. They were the previously healthy, strong and strapping late teen and early- twenties men. They were healthy children, their mothers, along with the anticipated tally of grandparents. The doctor would see them in the morning with early symptoms and return the next day to find them at death’s door.

Observing his overtired father ministering somewhat helplessly to these beautiful people, his own friends and neighbors, was sufficient inspiration for our protagonist to set a goal of becoming a physician himself—along with a promise never to overlook the human needs of his patients, and to do his best to fulfill the priestly role—as his father had so nobly done.

In that pandemic of 1918, often referred to as “Spanish Flu”, some differences regarding the present situation become apparent. A war was raging in Europe; there were military bases and camps throughout the country with soldiers living in dense proximity to each other, transferring locations and moving to the battle zones regularly. There had been previous influenza outbreaks in the 1890s but the etiologic agent causing the disease was not yet known. While polio had been correctly attributed to a virus by this time, influenza was thought to be a bacterial infection. In fact, Pfeiffer was assumed to have isolated the organism—today it is known as Hemophylus influenzae. There was no “flu vaccine”, there were no antivirals, no antibiotics, no computers to record and transmit the data as the process unfolded, and most importantly, there were no bedside ventilators to support the many victims who went on to die in respiratory failure. Supportive measures were all they had, and they were weak against this lethal foe.

In Connecticut, New London most likely provided the entry point for the virus since it was an embarkation point for troops leaving to fight in World War I. The pandemic took a toll of 8500 fatalities in the state; this out of one half million in the country, and estimates vary between 20 and 50 million fatalities throughout the world. The co-existing war constitutes a clear difference in comparing the two pandemics. As thousands were dying in their homes, shiploads of men were being transported to France to join the fight; soldiers were dying during transit at a rate and in a manner that sickened those who survived, and might be next.

Another major difference between the events of 1918 and the present was the total refusal of President Woodrow Wilson to address or become involved in the flu epidemic. His total attention was devoted to the war—not to be ended by a treaty but by total victory accomplished with the participation of the AEF. This mindset ensured that troop ships contained hundreds afflicted with the deadly virus were a seagoing flotilla throughout the entire pandemic.

Since there were insignificant pharmaceutical contributions to the anti-influenza efforts in the 1918 scourge, governments in the U.S. emphasized the importance of non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs. Lessons learned back then were re-instituted in the 2020 pandemic. In 1918, schools were closed, public gatherings were cancelled, isolation of the ill and quarantine of suspects was carried out. In the recent pandemic, all non-essential business entities were closed, laying off or furloughing employees. The earlier conduct in this regard was deemed in retrospect to have lowered disease transmission and mortality, and its validity guided governmental decision making in the recent pandemic.

As noted, one major factor distinguishing the earlier pandemic from more recent events is the management of threatening respiratory illness. The advent of the ventilator has contributed greatly to survival. We have learned, in the interval between the two episodes, a great deal about respiratory illness and death related to viral pneumonia. In the influenza epidemic, there were three distinct forms of pneumonia. The first was simple viral pneumonia, seen in its typical form even today in which there is primarily fluid accumulation in the interstitial tissues of the lung blocking adequate oxygen flow from alveolus to pulmonary capillary. It sometimes requires ventilator support to sustain life.

Some of the respiratory deaths in the 1918 pandemic were deemed to be the result of bacterial pneumonia, often yielding Pneumococci on sputum culture, but other bacteria, including the H. influenzae as well. In retrospect, this phenomenon was felt to be bacterial pneumonia superimposed on viral pneumonia. The third type of respiratory illness is ARDS, (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) which is sudden, often demonstrating “white out” of the lungs on chest x-ray and the demand for ventilator support to avert a fatal outcome. ARDS is considered to be the result of an overactive immune response.

Regarding the Coronavirus pandemic, intensivists estimated that the survival rate for those requiring a ventilator was 20-25%. This begs the question: what brings health care professionals to the bedsides of those stricken during one of these lethal tours of illness. When finding that more than three quarters of the patients placed on ventilators in any hospital’s ICU for the treatment of influenza or COVID-19 end as fatalities, we must salute those dedicated people who put their own lives at risk to do it, with dedication, skill and human compassion.

And, that level of commitment and empathy will continue to be an invitation to health professions that drew my friend and mentor, Dr. Leroy Wardner, at age nine, to follow in his father’s footsteps. Dr. Wardner, an obstetrician, became a member of the Hartford Medical Society and maintained an interest in the history of medicine through his membership in the Beaumont Medical Club at Yale School of Medicine.

About David Crombie, M.D.

About David Crombie, M.D.

Dr. Crombie was educated at Dartmouth College and received his M.D. from Tufts University School of Medicine. He trained in surgery at Hartford Hospital. He served in the U.S. Navy aboard the carrier USS Hancock during the VietNam War, as well as service at the Naval Hospital, Newport, Rhode Island. He had a career in general surgery at Hartford Hospital from 1969 to 2004, mostly as a private practitioner save for a ten year span in which he was full-time in the Department of Surgery. His leadership positions include: Chair of the Hartford Hospital Medical Ethics Committee, Director of the Department of Surgery (1994-97), President of the Hartford Medical Society, President of the New England Surgical Society (2001), Editor of Connecticut Medicine, The Journal of the Connecticut State Medical Society (1999-2011).