Rx: A Botanical Mother’s Day Bouquet

by Richard Ratzan, M.D.

Today marks my first blog on the HMS Library site. Like those of Jenny Miglus, Librarian of the HMS library, mine will be based on the materials in the HMS Library. We hope to continue to publish short essays of medical and historical interest for our readers and encourage them to use the wonderful resources here.

Mother’s Day

Observed since 1914, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the holiday (the second Sunday in May) into official status, the Mother’s Day movement actually began in the second half of the nineteenth century with Anna Reeves Jarvis, whose daughter, also named Anna, took up the cause after her mother died in 1905.

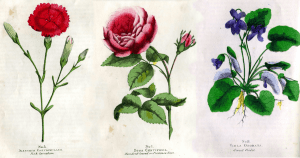

The Bouquet

Here, then, is our petite bouquet of flowers of both ornamental and medicinal value, which we offer to all mothers everywhere.

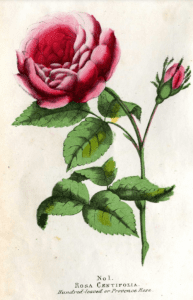

The Rose

No Mother’s Day vase would be complete without roses; a flower unique in historical, literary, romantic and medicinal annals.

No Mother’s Day vase would be complete without roses; a flower unique in historical, literary, romantic and medicinal annals.

As Peter Good so eloquently wrote in 1845, “The Rose is known by every one at first sight, and has been the choice and favorite flower – the queen of flowers – from time immemorial among the civilized nations of the earth. No flower, however, is more difficult to define than the Rose, and the difficulty arises in consequence of several curious facts in its natural history. The Rose is the only flower that is beautiful in all its stages, from the instant the calyx bursts and shows a streak of the corolla, until it is full blown. Again, there is no other flower that is really rich in its confusion, or that is not the less elegant for the total absence of all uniformity and order.” (Good, 1845)

Writers as diverse as Shakespeare (“A rose by another name would smell as sweet”) and Gertrude Stein, who was never so happy as when she was redefining the accepted canon, modifying, somewhat, the Bard’s line with “A rose is a rose is a rose,” have found the rose metaphorically as rich as it is beautiful. Medically, it has long been used for both ends of the body: “Slightly laxative,” the Rosa centifolia was felt to be an “excellent purgative for children; and for adults of a costive habit.“(Good, 1845).

Culpeper felt that a “decoction of Red Roses made with wine, [sic] is very good for the head ache, and pains in the eyes, ears, throat and gums; also for the fundament the lower parts of the belly and matrix, being bathed or put into them.” (Culpeper, 1826) p 210.

The Violet

Die blauen Frühlingsaugen

Die blauen Frühlingsaugen

Schaun aus dem Gras hervor;

Das sind die lieben Veilchen,

Die ich zum Strauß erkor.

(Heine, Martin, & Bowring, 1892) page 11.

The eyes of spring, so azure,

Are peeping from the ground;

They are the darling violets,

That I in nosegays bound.

(Heine et al., 1892) page 230.

The incomparable Heinrich Heine, who died at 58 from a disease that has variously been diagnosed, retrospectively, as syphilis, multiple sclerosis or lead poisoning, wrote these beautiful lines about violets almost 200 years ago in 1835.

Good records many uses of violets, from diuretic use to laxatives and recommends them as “. . . excellent in the gravel and all complaints of the kidneys and bladder. . . A decoction is frequently an ingredient in clyster for softening and lubricating the bowels.” (Good, 1845)

Culpeper notes their utility in the following: inflammation, eyes, womb, headache, choler, quinsy, falling-sickness, swellings, pleurisy, phlegm, hoarseness, throat, back, reins, bladder. Additionally, “The green leaves are used with other herbs, to make plaisters and poultices for inflammations and swellings and for the piles, being fried with yolks of eggs, and applied thereto.” (Culpeper, 1826) pp 246-7. Culpeper neglects to record whether such poultices, or their patients, are to be prepared “over easy,” as I would hope.

Nicholas Culpeper (1616 – 1654) was a very interesting physician, astrologer and botanist. Considered a radical for his iconoclastic beliefs about the right of public access to reasonably affordable health care and anti-establishment views about proprietary prescriptions, he was as ardent an herbalist as he was a principlist. His 1653 Complete Herbal, in continuous publication for centuries, made its way into Rudyard Kipling’s hands, inspiring the short story, A Doctor of Medicine, based on Culpeper’s life. (Vora & Lyons, 2004) He died in London of tuberculosis at the age of 37. [N.B. Dr. Lyons is none other than our esteemed HMS member.]

Anticipating the plastic surgical and botox branches of medicine by a few years, Good notes that “The Caledonian ladies formerly used the Violet as a cosmetic, as appears from the advice given in the following Gaelic lines:

Sail-chuach as bianne ghabhar

Suadh re t aghaidh,

‘Scha ‘n’eil mac ri’air an domhan

Nach bi air do dheadhai’.

Translation: Anoint thy face with goats’ milk in which violets have been infused and there is not a young prince upon earth who would not be charmed with thy beauty.” (Good, 1845)

The Carnation

The last flower in our bouquet is a carnation, known of old as a “pink.” We could write an entire blog on just the fascinating etymology of “pink” (Online Etymology Dictionary), “carnation” and “Dianthus,“ the genus of carnations. The last, “Dianthus,” derives from the compliment the ancients paid the carnation, calling it the flower (ἄνθος) of Zeus (Διός).

The last flower in our bouquet is a carnation, known of old as a “pink.” We could write an entire blog on just the fascinating etymology of “pink” (Online Etymology Dictionary), “carnation” and “Dianthus,“ the genus of carnations. The last, “Dianthus,” derives from the compliment the ancients paid the carnation, calling it the flower (ἄνθος) of Zeus (Διός).

Good writes that “The DIANTHUS CARYOPHYLLUS, or clove pink, is a flower too generally known to require minute description. It has long been deservedly esteemed both for its superior beauty and rich spicy odor . . .” (Good, 1845)

It was known as “clove pink” since “caryo” (κάρυον) means “nut” in Greek (Perseus Greek Dictionary) and was used (as “ξανθοκάρυον”) for the clove, the odor of which apparently resembled that of the carnation, leading to the latter’s name.

The carnation has proved of use, at least as of 1845 when Good wrote his Materia Medica Botanica, as “a remedy against the plague and other pestilential fevers …” It also was used for “headaches, faintings, palpitations of the heart, convulsions, tremors . . .” Good does acknowledge that “Modern practitioners, however, pay little respect to these opinions of their predecessors, and use the DIANTHUS CAROPHYLLUS only to give an agreeable flavor and fine color to a syrup, which is a pleasant vehicle for the exhibition of more active medicines.”

Even more modern practitioners, or, to be more precise, researchers, have found a potentially novel and much more important use for carnations than their dubious therapeutic value in faintings and convulsions. In fact, it may eventually turn out that Dianthus caryophyllus IS useful for pestilential fevers since its oils may prove larvicidal to Culex pipiens, a mosquito vector for Japanese encephalitis virus as well as West Nile Virus. (Kimbaris, Koliopoulos, Michaelakis, & Konstantopoulou, 2012). Or, as we say in botanical medicine, what goes around comes around.

HAPPY MOTHERS DAY!

Richard M. Ratzan, MD

References

Culpeper, N. (1826). The English physician enlarged : containing three

hundred and sixty-nine receipts for medicines made from herbs. Taunton:

Printed by Samuel W. Mortimer.

Good, P. P. (1845). A materia medica botanica, containing the botanical analysis, natural history, and chemical and medical properties of plants:

illustrated by colored engravings of original drawings, taken from nature.

New York; New Milford, Conn.: Published by J.K. Wellman.

Heine, H., Martin, T., & Bowring, E. A. (1892). Heine’s Book of songs (pp. 1

online resource (244 pages)). Retrieved from HathiTrust Digital Library,

Full view http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/811984.html

Retrieved from HathiTrust Digital Library, Full view

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/811984.html

Kimbaris, A. C., Koliopoulos, G., Michaelakis, A., & Konstantopoulou, M.

A. (2012). Bioactivity of Dianthus caryophyllus, Lepidium sativum,

Pimpinella anisum, and Illicium verum essential oils and their major

components against the West Nile vector Culex pipiens. Parasitol Res,

111(6), 2403-2410. doi:10.1007/s00436-012-3097-1

Vora, S. K., & Lyons, R. W. (2004). The medical Kipling–syphilis, tabes

dorsalis, and Romberg’s test. Emerg Infect Dis, 10(6), 1160-1162.

doi:10.3201/eid1006.031117